Kant and the Spirit of Revolution

The recovery of historic orthodoxy requires freeing ourselves from Kant's influence

Why is Immanuel Kant not a much more controversial figure in modern theology and philosophy than he is? Why is he seldom discussed by conservative theologians? The influence of his thought on modern culture is vast and it is almost totally negative. Not many figures in history have done more damage to Christian thought than he has done. Yet his influence continues quietly without much push back.

Who was Immanuel Kant?

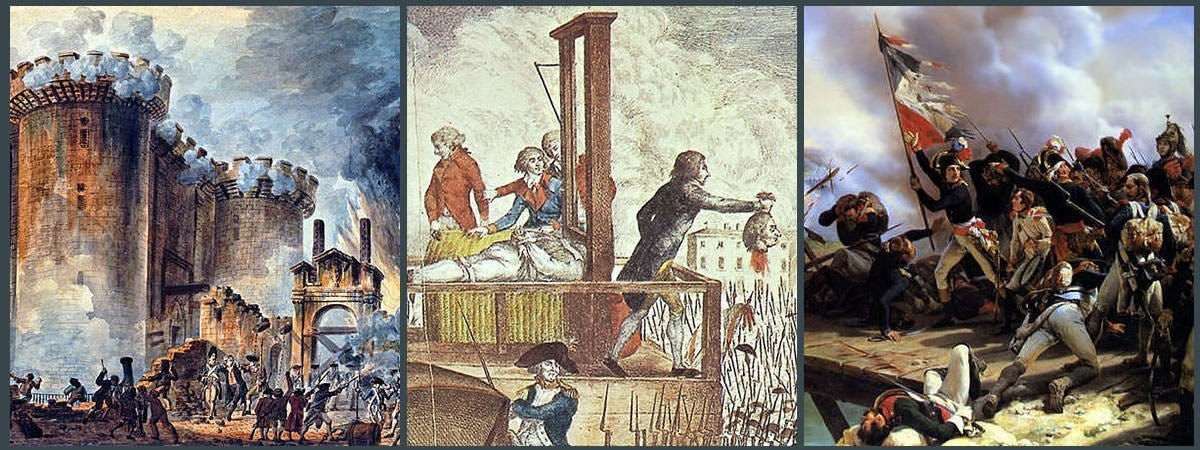

He is a bridge figure who stands between 18th century Enlightenment Rationalism and 19th century German Idealism and Marxism. In many ways he is the quintessential Enlightenment figure; his death in 1804 is often cited as the end of the period of the Enlightenment. He exalted reason above faith and sought to merge empiricism and rationalism. Yet, he also was highly sympathetic to the romantic and Utopian ideas of the French Revolution despite living through its worst excesses. He wanted the ideals of the French Revolution – liberty, equality, and fraternity – to be embraced by his own German culture as well as in France. Yet he is not usually perceived as a political philosopher and part of the reason for that is that he lived in a reactionary society that forced him to keep his head down. His works were always in danger of being censored, and some were censored by the state. Although he is in many ways an icon of the Enlightenment, he is also in other ways an important figure for Romanticism and Utopian ideology.

Kant was impressed by the sophistry of David Hume to the point of believing that Hume was right to dismiss classical metaphysics including the principle of causality. This is very curious because Kant was a man of science who trumpeted the superiority of reason to faith in every way possible and the principle of causality is, after all, the very basis of science. Things in nature do not happen randomly but only as a result of a cause. Believing in this principle is what gives scientists the incentive to conduct experiments seeking the unknown causes of phenomena. There must be a cause for every change in nature even if we don’t see it right now or understand it. Faith in the principle of causality is actually faith in the rationality of the cosmos. Apart from this conviction, there is no reason to have confidence in scientific research as a means of discovering the truth about reality.

Hume denied the principle of causality in his work, A Treatise on Human Nature, published in 1739. It was, in many ways, the culmination of the Enlightenment’s rejection of classical metaphysics. Hume rejected the realism that had characterized the Platonist tradition for over 2000 years in favor of an extreme nominalism. For Hume universals are not real. He also promoted the Enlightenment’s embrace of mechanism by holding that efficient and material causes constitute a sufficient explanation for natural phenomena, while formal and final causes are not necessary to a scientific explanation. The world is not designed by God, and it has no ultimate purpose. When you understand the mechanical and material processes by which something happens you have understood all there is to understand. The “why” question can never be a matter of fact; it is only a value, which is to say that all questions of purpose and meaning are merely subjective opinions or feelings. Both nominalism and mechanism grow out of the Enlightenment’s repristinating of ancient Greek materialism. The cosmos that is accessible to our five senses is all that exists. How do they know this? It is really a matter of faith for Enlightenment neo-paganism.

In Hume’s Dialogues on Natural Religion, we perhaps see the reason why he was willing to risk undermining science by denying the principle of causality. It was the only way he could rationally hold to his atheism. If the principle of causality is true, God must exist because the change we observe going on in the world around us requires a cause and the causal chain leads us to a First Cause. But if we deny the principle of causality, then we have no need for “the God hypothesis.” Ironically, the result of the Enlightenment denial of God was that science was undermined as well.

Kant believed that Hume had demolished classical metaphysics and he realized that without classical metaphysics the foundations of science were in jeopardy. To his credit, he saw this much more clearly than anyone else in his day and he was acutely aware that some new foundation for science was required. He saw that a new age was dawning and that the future must necessarily be very different from the past.

The Critical Philosophy

So, Kant set out to construct his critical philosophy as a new foundation for human knowledge including natural science and ethics. He sought to replace classical metaphysics with something new. The old metaphysics was the basis of ethics (natural law), religion (natural theology) and science and technology (the principle of causality). But Kant’s new system had to be built on the basis of materialism, nominalism, and mechanism. Going forward, the assumption would be that nature does not disclose its own meaning to human reason. Nature is merely a number of individually existing things that exist separately and not in hierarchically arranged groups based on the participation of things in universals. Each thing has its own unique nature, so to know a thing’s nature is to know only that one thing and not the category of things with which it shares a common nature. Thus, it is up to the human mind to impose order and structure on nature.

In sharp contrast to the Platonist tradition, Kant held that we cannot know the natures of things, that is, the “things in themselves.” We can only observe appearances, but the thing’s inner being is hidden to us – if, that is, things even have an inner being or nature. Who can say? In classical metaphysics we know how to predict the behavior of a thing in the world insofar, and to the extent that, we know its nature. It is the nature of water to freeze at 32 degrees Fahrenheit, for example. Once we know what a thing is, we can say quite a lot about it and apply that knowledge to its interaction with other things. What we call the “laws of nature” are descriptions of how the natures of things cause them to behave. Technology, or applied science, is made possible by our knowledge of the natures of things.

But for Enlightenment thinkers we do not need a teleological definition of a thing that explains why it is what it is. All we need is the material and mechanistic explanation of how it works because that is all that is required in order to develop technological applications of science. In modernity, science has been reduced to what we need to create technology because science has morphed into a quest for power rather than a quest for wisdom. Originally, science arose out of classical metaphysics and technology then became possible on the basis of natural science. In the late modern West, however, technological progress continues on the basis of a science that is no longer understood to be the truth about nature. It is merely a disconnected group of theories that happen to work. Technology continues to flourish even as science, in the sense of true knowledge of reality, withers. How long this can continue into the future is not clear at this time.

Kant has a reputation for being difficult to understand and his writing is full of jargon and impenetrable prose. Many people assume that the reason for this is that he is so profound and above our comprehension. But, in fact, it is really because he is trying to square a circle and do the impossible. His critical philosophy was a failure. Or, to put it more precisely, he influenced subsequent generations primarily by means of what he denied rather than by means of what he affirmed. His influence consists in what he tore down (classical metaphysics) not what he built up (the critical philosophy). Even those who sought to create an alternative to his critical philosophy (like Hegel, for example) often assumed that in rejecting classical metaphysics Kant established the ground rules for how any future philosophy would work. Even his opponents felt they had to meet him half-way, which is why one often encounters conservative theologians and philosophers today who call themselves “critical realists.” (See, for example, N. T. Wright’s, The New Testament and the People of God, Ch. 2)

German Idealism and all the major schools of philosophy in the past two centuries, both in Europe and in the Anglo-Saxon world, have been influenced by the rejection of classical metaphysics by Hume and Kant. Philosophy since Kant has been a restless search for a way forward that has focussed on epistemology, rather than metaphysics, in a desperate attempt to ward off the spectres of skepticism, relativism and nihilism. But philosophy has failed in this quest and existential despair now pervades Western society. As a result, our culture is disintegrating. Nietzscheanism was the direct result of philosophy’s failure.

The Spirit of Revolution

If one phrase were to be selected to sum up post-Kantian thought, it would have to be “the spirit of revolution.” This is what the Jacobins of the French Revolution, the Bolsheviks, the Maoists, and the later postmodernists all have in common. It is the driving force behind the various ideologies that came to dominate the twentieth century. It is a manifestation in history of what Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor called: “The wise and dread spirit, the spirit of self-destruction and non-existence.” (Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, Ch. 5) But what was its appeal? Simply put, it offered power to the powerless - power that could be used for revenge.

The whole effect on Western culture of the radical French and Scottish Enlightenments was to “debunk” tradition, monarchy, religion, the church, natural law, and morality. Caught up this storm of passion, the very metaphysical foundations of civilization were dismissed as private opinions, myths, and superstitions. We can see the radical force of this “debunking” today in the extreme iconoclasm of ideologies such as postcolonialism, deconstruction, and critical theory.

Critical theory is a form of post-Kantian constructivism. It is basically the idea that all social institutions, laws, and traditions are nothing but rationalizations of existing power structures. Therefore, they have no inherent moral legitimacy. If we are strong enough or devious enough to tear them down, then they deserve to be torn down. Injustice is redefined to mean whatever is inconvenient or detrimental to me or my group. So, critical theory seeks to destabilize, desacralize, and deconstruct whatever social institutions or traditions stand in the way of total revolution. A naïve Utopianism, often associated with the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, promises that when we burn it all down whatever emerges from the rubble will inevitably be better. But the deception is that when they say “better” they do not mean “more just according to objective criteria.” Instead, they mean “a new unjust order that it better because it is ours.” The radical narcissism of critical theory is that the self becomes the measure of all things. The maxim of the ancient sophist, Protagoras, is resurrected in the new sophism and man - specifically, the “Self,” becomes “the measure of all things.”

Almost all of what is called philosophy after Kant is not really philosophy in the Platonic sense of a love of reality-based wisdom; it is what Plato called “sophism.” The Sophists were teachers who claimed to be able to teach ambitious young men from the leading families of the Greek city states how to win arguments in public debates. They claimed to teach skills that one could use to win cases in the courts, get elected to public office, and sway the masses to go along with one’s will. Long before Nietzsche, the Sophists were peddlers of what Nietzsche called “the will to power.” The twentieth century was not dominated by competing schools of philosophy but rather by competing ideologies. Communism, Fascism, Progressivism, Liberalism – these are all ideologies. None seek to learn the nature of the Good by understanding reality; instead, they all seek to impose human will on the raw material of nature to shape Utopia according to the individual wills of the most powerful.

It was a stroke of genius that led the neo-Calvinist party in the Netherlands to choose the name “the Anti-Revolutionary Party.” Abraham Kuyper was clear about the true nature of the enemy. He understood better than most contemporary Christians that the beating heart of modernity is the spirit of revolution, and that the arbitrary imposition of human will on nature and society is the essence of the spirit of Antichrist.

Conclusion

We need to grasp the point that Kant’s critical philosophy is an expression of the spirit of revolution that animated the French and Russian Revolutions and led to the horrors of twentieth century totalitarianism. In its rejection of the principle of causality and classical metaphysics in general it is essential irrational. Ironically, the supposed pinnacle of Enlightenment rationalism turns out to be romantic and nihilistic at its core.

This means that we need to reject Kant and come up with an epistemology, a metaphysics and an ethic that is not vulnerable to the critical acids of his critiques. Meeting him half-way is not an option. This is the biggest challenge facing any Christian philosophy or theology today and if it is swept under the rug or dismissed as unimportant the inevitable result will be that Kant’s negative influence will undermine all our attempts to speak truly of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. Our talk about God will be hollow. Our account of reality will not be taken seriously.

If we wish to do serious philosophy and theology in the twenty-first century, we must free ourselves of the negative influence of Kant. In my opinion, the best way to do this is to find another philosopher who is as comprehensive and as radical as Kant on metaphysical questions but who has answers that are compatible with Christian orthodoxy. The best candidate, so far as I can see, is Thomas Aquinas. This is why I tweeted the other day:

“Increasingly, it seems to me that the choice for theology is stark: either one accepts Hume and Kant and proceeds down the road to skepticism and nihilism or else one returns to Thomas Aquinas. If Thomas is unthinkable, nihilism is inevitable.”