It is no exaggeration to say that the Western church is as much in need of reformation today as it was at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Roman Catholicism still needs drastic reforms, having largely rejected what was offered in the Reformation. Protestantism has drifted from its roots and to a very great extent lost its catholicity. The Evangelical movement has tried to revive nominal Protestantism since the 1730’s but it has failed to maintain a firm hold on the reformation era confessions and thus has drifted theologically. We are losing our grip on the Trinitarian and Christological orthodoxy symbolized in the creeds of the undivided church of the first five centuries. The situation today, like that of the late medieval era, is ideal for the rise of heresies of all sorts.

Satan lacks the ability to create anything totally new, so all heresy is parasitic on the truth. Heresy always involves twisting, eviscerating, or adding to true doctrine. As the Preacher observed three thousand years ago, there truly is “nothing new under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9). Heresy is usually constructed out of whatever building materials happen to be available in each cultural situation. Elements of the pagan religion of Egypt aided Aaron and the people of Israel in the construction of the first idol at the base of Mount Sinai (Exodus 32). The Baal worship of the Canaanites was combined with Israelite religion in the time of Elijah (1 Kings 18:21). The trendy, Eastern cosmology from Persia was used by Marcion and other gnostics in the early church to create gnostic forms of Christianity. Heresy usually involves drawing in ideas, symbols, doctrines, practices, or deities from the religion of the surrounding culture and combining them in some novel fashion with biblical truth to form a new kind of religion.

If this is true, how does heresy take form in a secularized Christendom? It seems that even though non-Christian forms of religion exist in the late modern West, moderns view themselves as post-religious and thus are unlikely to be drawn into a new form of religion constructed out of non-Christian and Christian elements. Do we not live in a post-religious age?

We should not to jump to conclusions on this point. The secularization thesis has fallen on hard times over the past forty years and what seemed obvious to secular-minded observers in the 1960’s is now uncertain and unclear. What is clear is that Western culture is increasingly hostile to catholic, orthodox, Christianity. But it is less clear to what degree the late modern West is really secular. This ambiguity is evident in talk of the “secular religions” such as Communism, Nazism, and Fascism.

Liberal democratic nations, rooted in Christianity, defeated the totalitarian ideologies in World War II and the Cold War, but since 1945 the national religion of western European countries and the anglosphere has undergone massive changes. The best way to describe what has emerged is to speak of it as a new Christian heresy. An heretical form of Christianity has become dominant in the West and pushed catholic orthodoxy into the background as a continuing minority, which is able to exert less and less influence on the culture. The so-called “culture wars” are the imperialistic wars waged by this Christian heresy against the forces of tradition, catholicity, and orthodoxy within both the Roman Church and Protestant churches, and also within Evangelicalism. There are pockets of resistance to this heresy within certain segments of Roman Catholicism and Evangelicalism, but the “mainline” Protestant denominations have been almost totally corrupted by it.

It is easy for conservatives to sneer at the declining numbers of liberal Protestant churches and assume that their cultural influence is negligible. Yet, the law and public opinion keep changing in lockstep with the pronouncements of the liberal clergy and conservatives keep losing court cases, legislative battles, and public opinion polls. It must not be overlooked that many Roman bishops, having noted which way the wind is blowing, have aligned themselves with the growing heresy in order to keep up to their flocks. Liberal theology is as much a problem in the Roman church as it is in any of the Protestant ones. It is difficult to see much difference these days, in practical terms, between the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Both espouse the new heresy and work tirelessly to see it triumph.

The Heresy of Progressivism

So, what is this heresy? It is, quite simply, the heresy of progressivism. Progressivist Christianity is the new post-catholic, post-protestant, and post-biblical form of Christianity that has swept to power in the late modern west. Like the Golden Calf cult, Baal syncretism, and the Gnostic churches of the early centuries, this new heresy is a synthesis of elements drawn from the surrounding culture and fused with elements of biblical teaching in such a way as to contradict biblical orthodoxy. The key point is not that the new doctrine draws in ideas and practices from outside of biblical faith, but rather that it does so in ways that fundamentally corrupt biblical faith.

There was nothing wrong with the Israelites borrowing from Egyptian religion. God himself copied the portable worship centers, which existed in Egyptian religion, in commanding Israel in Exodus 25-40 to build a tabernacle for Yahweh worship. The floor plan was a design common in temples throughout the ancient Near East. Israel’s tabernacle, however, had no idol in the holy of holies in accordance with the Second Commandment. The creation of the Golden Calf in Exodus 32, on the other hand, was a violation of the Second Commandment and thus is an example of a borrowed practice that could not be reconciled with the Law. The point is that sometimes borrowing non-Christian elements of religion fundamentally corrupts the Christian faith, and results in heresy.

It is, therefore, of crucial importance that theologians clarify for the church what cannot legitimately be borrowed from the culture, but must instead be opposed steadfastly by the church. Many elements of the culture are good or neutral and can be incorporated into the Christian faith. But not all. Discerning where is the line between assimilating and being assimilated is one of theology’s most important tasks.

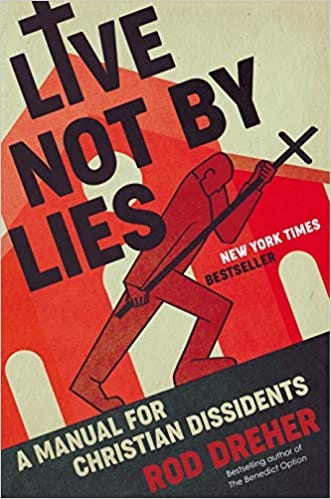

One example of potentially dangerous cultural borrowing that we see in the twentieth century is the embrace of the Marxist idea of what Rod Dreher (quoting Milan Kundera) calls “The Grand March toward progress.” (Live Not by Lies, 49) Is mankind on a “Grand March” toward brotherhood, equality, and social justice? Is it true that the modern man is closer to realizing heaven on earth than any previous civilization? Is total and complete social justice a real human possibility out there waiting for us to dare to seize it? The Social Gospel of the early twentieth century, the Liberation theology of the mid twentieth century and the woke progressivism of today all have flirted with this deadly idea. A century of murder, war, tyranny, dehumanization, and genocide stands as silent testimony to the inability of man to irradicate evil from his own nature, let alone from human culture.

The Central Tenets of Progressivism

In his recent book, Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents, Rod Dreher has a chapter entitled “Progressivism as Religion” in which he argues that the essence of modernity can be stated in the formula: “modernity is progress.” This concise thesis means that the very heart of what is often called “the modern project” originating in the so-called ‘Enlightenment,’ is the idea of human progress as infinite possibility. No limits on human progress exist because humanity is not fatally flawed by sin, as orthodox Christianity teaches. Instead, humanity possesses the knowledge and potential to realize heaven on earth if only the regressive enemies of progress can be neutralized. Many of the conflicts in our current society can be traced back to an aggressive war against conservatives who are perceived as standing in the way of progress.

Today’s “cult of social justice” (Dreher’s term) is populated by heretics infused with a sense of their inherent righteousness and absolute certainty about the moral superiority of their vision. Here are some of the main tenets of the progressivist creed as listed by Dreher (pp. 60-65).

1. The central fact of human existence is power and how it is used.

There is a large difference between authority, which requires legitimacy from nature or God, and pure power, which is its own authority. For the social justice warriors all of life, including all social relations, is understood as manifestations of power. For them, authority is reduced to raw power.

2. There is no such thing as objective truth.

This is an implication of the first point, but is worth singling out because of its importance. Epistemological and moral relativism are accepted as basic elements of the progressive creed, even though relativism ultimately undermines the idea of progress insofar as it eliminates any objective standard by which progress could be measured. This contradiction is simply ignored.

3. Identity politics is the way to sort the oppressed from the oppressors.

In a relativistic creed that rejects objective truth, some basis for “social justice” is nonetheless required and identity politics fills the gap. Identity politics is basically a way to identify enemies and justify taking power away from them. Like ancient Manichaeism, it uses a superficial and utterly arbitrary method of dividing the world into the “good guys” and the “bad guys.” Since progress can only come by the use of raw power, there needs to be some way of justifying the use of violence and coercions against those styled “enemies of progress.”

4. Intersectionality is social justice ecumenism.

It is a way of forming alliances of activist groups against the status quo. It is also irrational. For example, how is it reasonable to regard a white, Pentecostal man who lives in a trailer park on a disability pension as an oppressor and a black, Ivy League university law professor as a member of an oppressed minority? It is utterly irrational, but the point in progressivism is not to analyze society in accordance with some notion of objective truth because there is no such thing as objective truth (see #2 above). The point is to manipulate emotions and form alliances against the conservative enemy by whatever means works. And appealing to the sin of racism works.

5. Language creates human realities.

This point explains how the previous one works. By labelling identity groups and painting society as systemically racist, language creates reality. We see this every time a Twitter mob attacks a new scapegoat. The passion, the emotion, the furor – all this itself becomes the reality. Whatever the person did or did not do and the facts of the case are mostly irrelevant. This is why there is no concern for due process. To be “credibly accused” is itself a reality that becomes a club with which to beat the enemies of progress.

These are central tenets of progressive Christianity. How do they stack up against historic orthodoxy?

A Theological Evaluation of Progressivism

Space does not permit anything like a comprehensive evaluation here. But I want to make two quick point to show how heretical progressivism is.

Progressivism teaches eschatology without Christology.

Progressivism teaches that the kingdom of God – heaven on earth – can and will come through human ingenuity, especially, by certain human beings wielding absolute power over other human beings. Progressivism borrows its eschatology from Marxism and clothes it in biblical terminology to make it plausibly Christian.

Christianity has taught continuously since Paul wrote the letters to the Thessalonians around AD 50 that the final judgment (the Day of the Lord) and reign of peace and justice (the kingdom of God) can only come as a result of the personal, bodily, return of the Lord Jesus Christ on the clouds of glory. Christian doctrine is adamant on this point, despite divergences in eschatological theories. The one point that all orthodox eschatological schools share is the point made in the Apostles’ Creed: “from thence he shall come to judge the living and the dead.” To turn this into “we can bring social justice by identity politics” is to reject the Creed and substitute a heresy for catholic doctrine.

Salvation comes by Christ. Could any doctrine be more fundamental than this? In progressive Christianity Christ is no longer Savior; he is at most an example or a hero. But the essence of progressivism is that we do not sit around waiting for him to save us – we get busy and save the world ourselves. The apostle Paul, writing to the Thessalonians, says that they have become an example of faith because “you turned to God from idols to serve the true and living God, and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead, Jesus who delivers us from the wrath to come.” (1 Thessalonians 1:9-10).

Progressivism is heretical because it teaches that we find salvation through our own efforts rather than through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. It is thus completely and utterly opposed to the essence of Evangelicalism and its stress on the need to be saved by faith in Christ.

Progressivism substitutes false guilt and shame for true moral guilt.

It does this by denying metaphysical realism, which is the framework in which the doctrine of original sin makes sense. By denying objective truth progressivism undermines the entire structure of sin and salvation taught in Scripture. The social justice warrior identifies with the currently fashionable victim groups in order to justify himself as not needing salvation. Identifying with victim groups allows one to use violence, coercion, and control. The one who identifies with the victim claims the moral right to use power.

In Christianity, only God can be trusted with the task of ultimate judgment because human beings are all fallen sinners in need of salvation themselves. We all stand before God as sinners whose only hope in in Christ. None of us are sufficiently free from sin to be qualified to judge our neighbor. This means that in a Christian society true political and legal authority comes from God and so there should be a division of powers. This allows one branch of government can check another and prevent absolute power from falling into one set of hands.

The Christian doctrine of original sin leads directly to a division first seen in Israel with the rise of prophets to confront the kings and priests with God’s Word and later worked out in Christendom with the division of powers between kings, parliaments, and the judiciary. Progressivism is dangerous because it does not subordinate human power to divine authority and seek to destroy systems by which the various elements of human government operate as checks and balances on each other. Progressivism sees such systems as inherently conservative and seeks to destroy them.

Such systems were designed for a fallen world populated by sinners who must be restrained. The premise of such systems is that fallen human beings can never attain eschatological justice in this age. It assumes that we “wait for his Son from heaven.” But progressivism calls this kind of restraint evil and seeks to destroy it.

According to progressives we are always in an emergency situation that requires bold action and trampling tradition. Why? Because progressivism demands heaven here and now and shames anybody who tries to resist its utopian agenda. Even though it portrays itself as all about “justice” if we take its own claims seriously, we must conclude that it cares nothing for justice except as a concept it can use to attain total power. The spirit of progressivism is exactly the danger that Christianity recognizes in its insistence that man can never save himself. If progressivism is left unchecked, it will eventually destroy western culture. Heresy is not a private matter; it is a matter of life and death.